Chris Tomlin

In this study we use 3 versions from YouTube's most viewed "Amazing Grace" videos.

First we have the Amazing Grace by Chris Tomlin - GRAMMY award winner and Top Billboard Christian Rock song writer and singer.

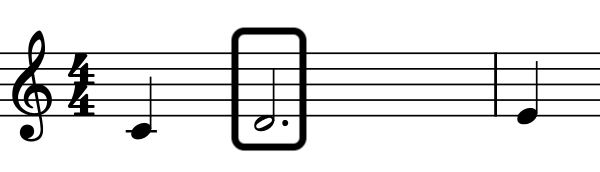

What is interesting about this version is how it changed the time signature from the original 3/4 time to 4/4 time, and the added new chorus that extended the motif of the chord progression. More about these in the commentary below.

Amazing Grace Chords

Celtic Woman

This second version of Amazing Gracing is by Celtic Woman an award-winning Celtic Folk vocal group topping multiple Billboard charts. Worth a note is its 2 occurrences of key modulations. The first one goes up one whole step from F to G, but then backs down 2 whole steps to Eb. Find these 2 changes in the YouTube video (2:24 & 3:14), and read more in the commentary below.

Amazing Grace Chords

Pentatonix

Pentatonix is an A Cappella Beatbox vocal group famous for their rearrangement of classic hits and Christmas songs. The cover of Amazing Grace combines the traditional hymnal version transitioning to Chris Tomlin's pop rock "My Chains Are Gone" rendition. Read below to learn more about this transition.

Amazing Grace Chords

MELODIC ANALYSIS

To arrange our own chords for a song, besides just by feeling them through trial-and-error, there are methodic ways. It can be done by analyzing the notes and shape of the melody. This analysis can reveal patterns and points of interest of the melody. Doing so helps us plan musical ideas in terms of chord progression. It helps us explore new sounds, for example, adding dissonant harmony that then resolves to fulfill a cadence of the melody.

Melodic Main Notes

The first step is to identify the main notes that the melody stays on. The purpose is to boil down the melody into a bare skeleton that still carries its essence. This helps us focus on the notes that have substantial effects harmonizing (or disharmonizing) with the accompanying chords. This takes out the passing notes, which are too brief to form the harmonic impression with the chords. Then, with the main notes identified, we can match them with chords.

How to identify the main notes

To identify main notes along a melody line, we look for the ones that leave a stronger impression to the listeners. In other words, they "stand out" the most.

Here are some characteristics to look for:

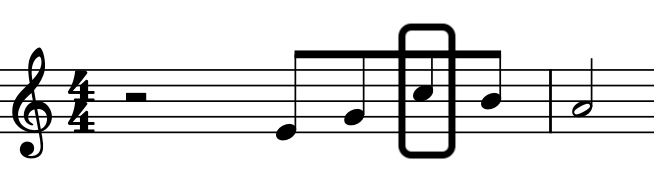

Long duration note:

because it leaves a longer impression to the listener.Downbeat note:

beat 1 of the bar, and also usually the midpoint of the bar. This is where the sense of rhythm is emphasized.Repeating notes:

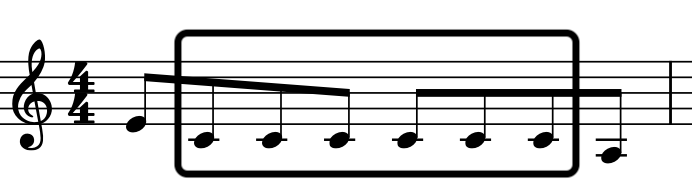

likewise, repetition gives a stronger impression and emphasis.Peak note:

a note that is higher in pitch than its neighbors, and therefore sticking out for them. The change in direction from up to down carries strength, which gets stronger when the intervals between the peak note and its neighboring notes increase.

Here are some examples:

-

Long duration note

-

Downbeat note

-

Repeating notes

-

Peak note

Amazing Grace's main notes

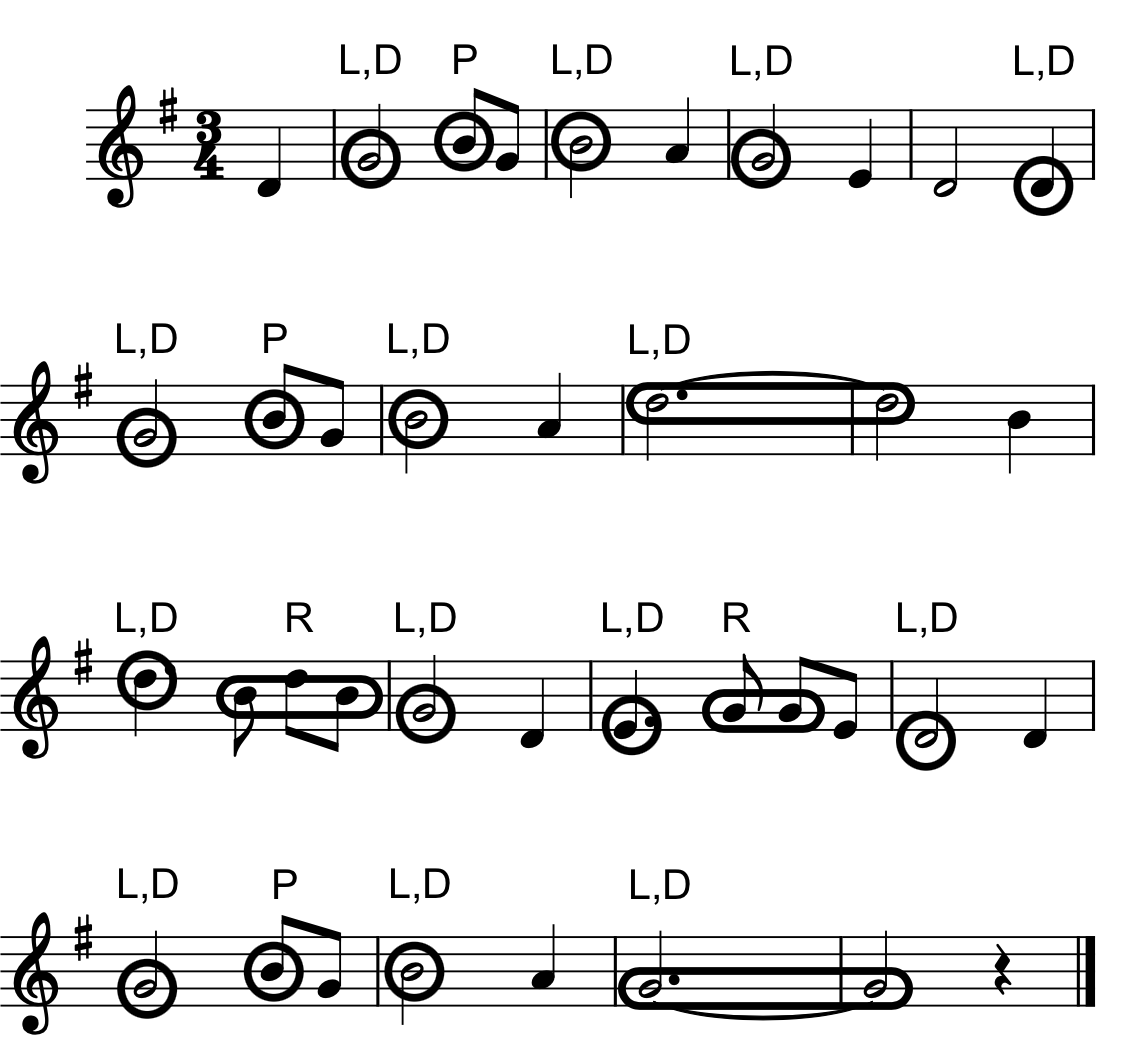

With the traditional Amazing Grace melody as an example, let's find out its main notes. For this song, all the downbeat - ie, beat 1 of the 3/4 time - are also the long duration ones. This conveniently gives us all the main notes, circled below.

Legend: L=Long; D=Downbeat; P=Peak; R=Repeating;

Now let's keep only the circled ones to show the skeleton of the melody:

Or in form of note numbers, further simplified:

From this trimmed down structure, we have some observations of the melody:

- All, except one of them, are 1-3-5 (eg C-E-G).

- Line 1, 2 & 4 starts with 1-3, while line 3 starts with 5-1. It looks like a A A B A form.

- All first 3 lines end on a 5, and then the last line ends on a 1. So the lines first repeatedly end with imperfect cadence, then finally the ending is fulfilled with the perfect cadence.

Example: Chord Pedaling for Amazing Grace

From the first observation, all except one of the main notes falls on the root chord 1-3-5. Does it mean that the whole song (or most of it) can naturally harmonize with the root chord, ie, the C chord in this C major example? Let's find out by playing the following chords for the song. Try it slowly and listen closely the harmony and the mood change along the song:

Chord Pedaling Example

Personally, this constant rows of C chords throughout the song brings me a sense of steadiness, calmness, and safety at home. (1-3-5 is the "home chord" after all). How appropriate it is to accompany the lyrics "and Grace will lead me home"!

In music theory, repeating the same bass line and/or the same chord along an extensive passage of melody is called pedaling

A pedal note reiterates the same standpoint even though the melody moves through main notes that outline a progression of chord changes. This sense is stronger especially when the melody is at discord with the long holding chord, building up the tension with the holdout - therefore the conviction - that craves for a resolution.

But the pedaling of Amazing Grace is different. It does not create discord, but rather stays harmonious throughout the song. This is the opposite effect - a soothing, lingering air of concord harmony. Even when without accompaniment, the melody itself hovers most of the time on 1, 3 and 5 (do, me, sol), imprinting the home-staying root chord-I to the listeners. In other words, the whole melody is already harmonizing itself - one main note harmonizing the next one, which in return harmonizes its next. This effect is more pronounced in solo performance with a long reverberated sound stage, when the lingering reverb of a main note echoes with the next note in perfect harmony.

Staying on the same chord, however smoothing it may sound, can quickly turn into lukewarm blandness. It calls for a break, which takes place at the IV chord (ie, F major chord) around the two-third point in the song.

It leads back to the same I-chord, creating a sustain-resolve motion, a plagal cadence for a smooth and graceful settlement. It is worth noting that usually such elevated, enlightened mood change (up from chord-I to chord-IV) creates a lifted ground leading up to a strong anticipation for a grand(-er) resolution. This is a climax effect, which goes especially strong at the two-child climax point of the song. But at that point (bar 11-12) the melody is at the low note range (reaching the lowest note of the song). This, contrary to the brief VI-I cadence, gently balances out the climax effect.

As a result, the downbeats of Amazing Grace build up a mostly static chord progression that conveys a sense of peace & anchoring meditation. It ushers a gentle movement that briefly expands the stillness, and retreats back to the I-chord for the homecoming finish.

Melody Contour

How to identify melody contour

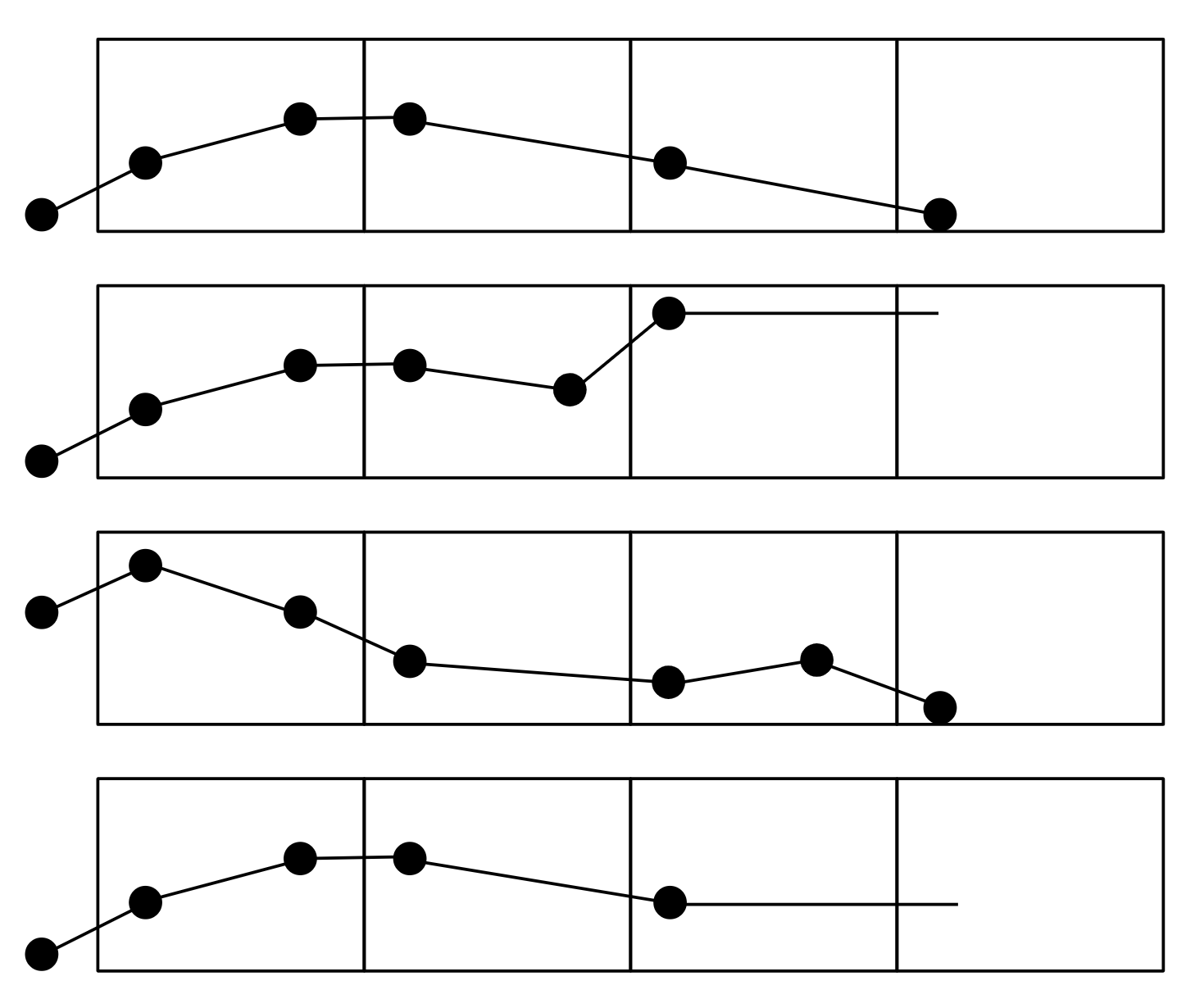

With the melody main notes identified, we can link these dots with imaginary lines to form a melody contour. It outlines the rough shape of the melody, ignoring brief passing notes. The purpose is to give a broad view of the change of intensity, points of interests and patterns in the melody.

Seeing the melody contour is helpful for chord arrangement. Chords can then be placed in a progression in parallel or contrary to the contour, to highlight a climax point, to animate a plateau, to still a melodic movement, etc. With this, chords are arranged with the horizontal flow of the melody line, not just vertically harmonizing note by note. This instills a narration element into the art of chord arrangement.

Let's use Amazing Grace as our example.

Amazing Grace's melody contour

Following the melody contour below, hum the "amazing grace" melody and see if you can match the dots to the notes you sing. Each rectangle represents a measure in 3/4 time signature.

Look for the lowest points. For singing, usually lower notes are more restful (unless it is uncomfortably low). We can see that every line touches the lowest note ("sol" below the root "doh"). This answers why this song gives the sense of comfort and rest.

Riding the Melodic Peaks

Now look for the highest points. They are in the middle of the song. Try humming the melody while tracing the contour lines to feel the peaks. There are 3 peaks:

- Line 1: small peak

- Line 2-3: highest peak

- Line 4: small peak

This draws an overarching symmetry in terms of the high-low intensity. The first line and the last line each have a small peak. (In fact they share the same melody except for the addition of the last 2 notes on the first line.) Then in the middle part - line 2 and 3 - it peaks right in the middle.

Instead of rushing to the top note, the melody introduces a gentle rise and fall in the first line, spanning a 6-step interval, from low note 5 to 3, then back to low note 5. Its main notes station on the root chord triad (the 2nd inversion), going up then back down.

When we interpret the movement of a melody line is by intensity, ie,

- Upward intensifies

- Downward relaxes

Then line 2 repeats the first half of line 1, passing by the previous peak on note 3. But instead of backing down like the 2nd half of line 1, line 2 continues to rise to high note 5, and hold the melody there. It reaches the melody peak of the song right in the middle of the stanza. Reaching top intensity at the middle gives more room - half of the stanza - to gradually land back to the home ground.

Satisfying Symmetry

This half-up half-down pattern gives the song a steady rhythm - not quarter note per bar kind of rhythm, but one 8-bar section to another 8-bar section rhythm. This sets forth a long-spanning motion, slowly raising (after a relaxed break on bar 4) to the peak in the middle (bar 8); then slowly lowering (with symmetrical low point on bar 12) back to the tonic root note.

This satisfyingly smooth and elegant motion is like a tidal wave that invites the next cycle. Once the next stanza sets off the first note, it effortlessly rises to the next peak, and back down, all-ready for the third wave. This is the amazing wave that carries the song for the hundreds of years since inception, from Buckinghamshire to the world, graciously flowing like oceans across both the religious and secular worlds.

Ways To Harmonize With Chords

Using Only I, IV & V Chords

A simple but useful rule to find chords for a song is that all the notes can be harmonized by only the first (chord I), fourth (IV) and fifth (V) chord of the major scale. A major scale, aka diatonic scale, comprises the sol-fa names Do, Re, Mi, Fa, So, La and Ti. They are all the white keys on a piano for C major scale. Here are the chords that harmonize them:

| Note | Harmonizing Chords |

|---|---|

| Do | I, IV |

| Re | V |

| Mi | I |

| Fa | IV |

| So | I, V |

| La | IV |

| Ti | V |

Spelling the chords in C major:

| Note | Harmonizing Chords |

|---|---|

| C note | C, F |

| D note | G |

| E note | C |

| F note | F |

| G note | C, G |

| A note | F |

| B note | G |

So a simple way to approach chord assignment is to use only I, IV and V first. This creates a bright and simple sound yet carries strong movements that flow along the song. These movements are propelled by the cadence - the sense of resolution (or the lack of it) - when a chord leads to the next chord:

- Cadence between I and IV is milder, while I & V is stronger

-

Moving onto chord-I sounds complete and satisfying:

- V - I

- IV - I

-

Moving away from chord-I sounds incomplete and suspended:

- I - V

- I - IV

Now apply this to Amazing Grace, harmonizing with only the I, IV and V chords, in C major:

Using only I, IV, V

Play again. This time listen to the cadence at the end of each line. Feel the sense of resolution when it lands on the home-coming C chord, and the suspended feeling when it leaps away from C.

Now try a different set of chords. Using the chord table above, we use only I, IV and V chords:

Alternative set of I, IV, V

Isn't this sounding quite different from the previous set of chords? Instead of starting each line with the root chord C (chord I), VI and V are used. This sets out each line being off from the tonal center of C. With the ending cadence of each line that does not come back to the root chord. This builds up the home-coming anticipation along the whole stanza, then finally hits home to a complete home chord ending at the very end of the song.

Build Up the Suspense Using Chord Changes

To build up even more sustain for a more gratifying resolution, there are other ways to avoid the root chord until the end:

-

Changing the bass note of the root chord, ie, inverted chord

- Eg, C becomes C on E bass (C/E)

- C becomes C on G bass (C/G)

-

Substituting root chord with its relative minor chord

- C major become A minor (Am)

Here is an example modifying the above chart with inverted chords and relative minor:

Inverted Chords & Relative Minor

See that once the chord sets off from root C in the beginning, the root never lands back to C until the very end. Feel the cadence, especially at the ending of each line. It holds at the dominant chord G (the strong incompleteness of the I-V cadence) for 3 times, and then finally answers all the three by the finishing C chord, twice to confirm the resolution.

Smooth out the motions along the chordal notes

Most of the time, a chord hits the strong downbeat of a measure. Doing so over the whole song can sound rigid and mechanical, especially when the bass note jumps skipping notes on the scale. Adding the bass notes like in above chart remedy the rigidness by smoothing out the jumping bass.

Along with this idea, let's smooth out the chords even more:

Smooth out the chords

Now with the D bass added to measure 1, the bass line of line 1 goes smoothly up the scale: C to D to E, then to F and G.

The same stepping happens on line 3 as well, as a V-shape that keep the ending movement upwards: G to F to E to F to G

Note the motion from Gsus to G on line 2. Even though the bass G stays unchanged, there is still a strong movement in the harmonic tension. The sus (or "suspended") chord (the 1-4-5 notes on a major scale) gives an unsettling sound because the presence of 1 and 5 create a series of harmonic overtones not spacing evenly with the overtones of the 4 note. With the culturally accustomed harmony of the chord 1-3-5, this 1-4-5 chord hangs like a tilted picture frame on the wall, waiting for the gravitational pull to bring it back to level. This anticipated leveling is the 1-3-5 major chord. The G chord in measure 8 serves this purpose, resolving the suspension - however temporarily because it is not the true home C chord, which will finally come at the end of the song as the final resolution.

Chord Harmonization by Third Intervals

A relatively simple way to choose chords for a song is using thirds below the melody. Here are the steps:

- Identify the main note

- If it's a long holding note (usually lasting 2 beats or longer), it is the main note

- If it's a short/brief passing note, identify which note it aims to land on. That landing note is the main note.

- The first note of a measure is usually the main note.

- Add a 3rd below that note as the bass

- This bass is on the scale of the key, so the interval can be a major 3rd or minor 3rd

- Add a 5th (or sometimes a 6th) above the bass, so that it forms a chord triad with the bass note and the main note.

Exceptions: this 3rd-below-melody technique may not work in one of these situations:

- Start and end of a song: they usually use the root chord of the song key.

- End of a section (verse, pre-chorus, etc…) but not end of the song: it usually resolves with an incomplete cadence on V (5th chord) or IV (4th chord) or even vii (6th chord).

Harmonize by thirds example. See that all the bass notes are a 3rd below the melody main notes, except for the start and end of a section.

See it in the chord chart in C major:

Harmonize by Thirds

The storytelling power of chord arrangement

Chord arrangement not only harmonizes the melody, it also has a storytelling aspect. Chord progression creates interplay of sustain & resolve, heighten and relax, adventuring and homecoming. Temporal harmonic resolutions and then the next sustaining chords build up tension to the climax of the song, then lead to the final resolution. This development expands the listening experience from audio ecstasy into a story journey that captivates the listeners' hearts.

COMMENTARY OF AMAZING GRACE RENDITIONS

Celtic Woman Rendition

This Celtic Woman rendition of Amazing Grace is full of nothing by adventure. Its 4 stanzas dramatically develop from start to end:

- Peaceful rest (v1)

- Intimately harmony (v2)

- Intensifying suspension (v3)

- Amicable conviction (v4)

The 1st stanza

Notice the steadiness of the first stanza? It is because most of it stays on or very close to the root note F. From the F major chord, it briefly moves to IV chord (Bb major), then back to rest on Chord-I (F major). Even when it moves to Dm chord, the root stays on F forming a chord inversion.

The middle of the stanza (ending of line 2), which marks the end of the first half of the song, uses chord C/E. This chord is the dominant V chord in the F major key - a C major triad, but with bass E which makes it an inverted chord. This inversion provides a softer sounding cadence, while leading the bassline from F (in the previous bar) intimately close to E. If root C chord is used on this bar, the cadence will sound much stronger, breaking the intimate sound that's been lingering in this stanza.

As we enter the last line, the holding bass note C is released to the D bass of the Dm chord, sounding out the first fully minor tone. Then the dominant V chord, ie, Csus, builds up the anticipation to the homecoming F chord. But as a surprising twist, instead of landing on the root F chord, the last note of the stanza lands on the suspending IV chord. This dissatisfaction kick-starts the journey to the upcoming stanzas, which have more musical adventure in store for the listeners, who long to finally arrive home.

2nd stanza

After stationing around the root I-chord F in the first stanza, the chords in stanza 2 now travel further, but still centering around the root chord. In 4-bar phrases, each of them start and/or end with the root:

- I vi IV I

- I vi V V

- I vi IV I

- IV V I I

These 4 musical phrases form an A-B-A-C pattern:

- The first half (A-B) ends on V, a suspending imperfect cadence.

- The 2nd half (A-C) ends on I to resolve the suspense.

- The 2 halves create a partial symmetry (having the same A) and at the same time a balanced asymmetry (B and C are different but coupled a call-and-response pair)

These sets of chords are variations of the '50s progression I-vi-IV-V, which is an easy-listening, instantly memorable chord progression. Its chord changes are coherent due to the the common notes along them:

- I and vi: sharing common notes 1 and 3 (solfa name Do and Mi)

- vi and IV: sharing common notes 1 and 6 (Do and La)

- I, vi and IV: sharing common note 1 (Do)

So the 1st 3 chords hold on to note 1, then the 4th breaks the streak going to chord V, which is the immediate neighbor of chord-I on the circle of fifth, and has a very strong voice-leading attraction compelling it back to chord I. This leading-back to the I-chord I conveniently repeats the 4-chord phrase again and again.

In the stanza 2 of this Celtic Woman rendition, bass note and passing chords are added to further ease the flow of the chord changes.

As a result, The chord progression of this stanza is very inviting to the listener to immerse in the harmony within the chords and the harmonious ease moving along the chords. This musical beauty resonates with the lyrics declaring the "fear relieved" and the "precious… grace appears", resolving to the conviction of "the hour I first believed". A well crafted chord arrangement that artfully fits the song!

3rd Stanza

After centering on the root in stanza 1, and developing from it in stanza 2, now stanza 3 is uplifted to a new musical ground.

The first change - and the most obvious one - is key modulation. It goes from F to G major via the chord D7 at the end of stanza 2. D7 is the dominant chord of G so it has a strong cadence force leading to the new key. D7 is also the major version of the vi minor chord of F, and thus providing a brightened (major chord) context for the modulation. This 3 step modulation (chord F to D7 to G) effectively creates an uplifted grand entrance for stanza 3 to begin.

Secondly, not only the key is changed, the bass becomes a long holding note spanning 8 measures. Not only does it hold long, it holds onto the dominant V note (D). This dominant V suspends the mood, without resolving to the long-anticipated destiny of the root note G. This low D tone creates the contextual overtones of a D chord triad plus 7th, all of which unite a strong voice-leading attraction toward the homecoming root chord G. Very interestingly, note that the root chord G is never resolved in this whole stanza.

As the (upper) chords change, the unchanging bass becomes a non-chordal note that is dissonant against them. This builds up conflict that further intensifies the anticipation to the final cadence resolution. This is like opening an archery bow with the arrow ready to shoot but keep holding this open position. This builds up the tension (literally) and draws out the anticipation of whether and when the arrow will be shot out.

How well does it match the lyrical meaning - "the many dangers, toils and snares"!

Now the metaphorical music arrow is shot out on line 3, instead of resolving the long held D bass to its cadence-target G root, it lands on bass B (of the G/B chord)! This inverted chord continues the unsettling journey of stanza 3.

The third musical device that is used in stanza 3 is the cadence setup. The first 3 lines all end on chord V. Naturally, it would then flow to chord I. Listen to that in so-fa name: "so… so… so…", it should then go to a final "... do" (chord I), right? But surprise, surprise, while expected chord I, it lands on its relative minor chord vi. It is called deceptive cadence, this ending of V-to-vi is dissatisfying like a story's tragic ending.

Then comes the twist. The 4th line is repeated - becoming the 5th - as if to give the story a second chance by grace. Now the question is: is this ending really the end of this stanza? Or if not, how will the story turn out to be? To answer this, let's look closer to this 5th line.

LINE 5

The 5th line of stanza 3 is the turning point of the song leading to the climactic last stanza. First, to compensate for the dissatisfaction of line 4, line 5 is introduced as a 2nd attempt to hit home, perfectly matching the lyrics at that moment: "And grace will lead me home"!

But does it get home - chordally? No, it leads from D chord not to the home G chord, but to - another surprise - C chord! It's not as dissatisfying as the deceptive Em minor on the previous line. This C here is at least a more optimistically sounding major chord and is less tension-pulling as the dominant V from the home I-chord. (that's why the C chord here is called the subdominant IV chord in key.) But still, this C chord misses the target G.

Here comes yet another surprise. As the C could have conveniently descended down the scale back to G, ie, C - B - A - G. Instead, it detours on a whole tone scale stepping down from C to Bb and then to Ab. This stepping serves 2 purposes:

-

Grandness:

- In the diatonic scale, there are no consecutive tones that are all major chords. The only ones are IV and V.

- So hitting 3 major chords on 3 connected steps is a rare find. Together they amplify the bright sound of major chords, 3 times.

- Try that out on a keyboard: C major → Bb major → Ab major

-

The 3 notes are on the scale of Eb major

- Eb-F-G-Ab-Bb-C-D-Eb

- Going from C to Bb to Ab covertly modulates the G key to the new Eb major key, hovering around and then landing on the dominant V chord (ie Bb major) of the new Eb key.

This line 5 cleverly and artfully prepares the new key signature for the next - the finale - stanza.

4th Stanza

The Lower Yet Grander Sound

After transposing the song key down from G to Eb, through the 3-step segway of C-Bb-Ab chords, the now lowered key sounds Ironically elevated and grander. This is quite opposite to the common practice to raise the key for more tension and excitement. How lowering the key in this song, on the contrary, brings it to a higher musical ground? Other than the 3-step major chord setup for this stanza, there are 2 more contributing factors:

- Unison voicing: the bagpipe section enters in to lead the melody in unison. While there are harmony parts (vocal and the string section) supporting the lead melody, the joining force of this unison line dominates the tonal space. This creates a strong sense of solidarity and therefore the heightened sense of climax, and put the lyrics to the center stage.

- As the key is lowered to Eb major, the melody range is shifted down to between the Bb below the middle C and the Bb above. This is a comfortable range for both male and female voices. It invites the audience to sing/hum along. This opening of the floor for participation shifts the position of the audience from a spectating listener to a character inside the story. This change in perspective brings the music experience closer and therefore bigger to the audience. This is especially fitting for Amazing Grace as a congregational song that is traditionally sung with the congregation while being led by instruments in unison. It is an experience that points people to something (or Someone) bigger, like proclaimed by the song itself "When we've been here ten thousand years , bright, shining as the sun".

Returning to the '50s Progression

The stanza returns to the chord progression of stanza 2, ie, the '50s progression variation. The main notes of the melody (the long notes on the downbeats) are all on the chord triads, forming consonant harmony with the bass and the enclosing chords. This consonance sounds even more harmonious and pleasant to the listeners after the striving tension built up in stanza 3. This makes the return of the already pleasant chord progression even more cherishable. Note that this stanza uses the lyrics of stanza 1, which starts with Amazing Grace How Sweet the Sound - the ubiquitous lyrics hook and melodic hook of this world-renowned song.

With all of these elements happening at the same moment - grand key modulation, solidarity in unison, cherished harmony after the tension, song hooks - this stanza pushes the song to its climax.

Behold the power of chord arrangement! Even before instrumentation - ie the arrangement of instruments to voice out the music - the chord progression in itself is already infusing dramatic emotions to the song.

The Ending

After unfolding all the wonders, the arranger does not end the song with just one chord, but prolongs it with a 4 measure-long cadence.

Deceptive Cadence

Furthermore, before the ending, the last line "was blind but now I see" end on the relative minor chord (Cm) of the key (Eb). This is known as deceptive cadence, an effective device to signal a repeat of the last line (aka tag line) of the song. It works by intentionally missing the anticipated root chord (Eb major in this song) while harmonizing with a pessimistically sounding minor version (C minor). This stirs up more longing for a comeback of a gratified ending. It is commonly used in modern christian congregational song, as a device to repeat the last line of the song, which usually carries the key message and points to the hope of their faith. This repetition solidifies the conviction of the singers.

The 4-bar cadence

Finally, coming to the end of the song, on the last note on the word "see", the IV chord (Ab) suspends the mood instead of landing on the supposed root I chord (Eb). This sets up a plagal cadence - a IV-I movement that gives a gentle landing. Plagal cadence is also known as the "amen cadence" in the Christian music because it's commonly used in choral work to arrange the multi-part vocals for the concluding "amen" of a song, with the syllable "a" on the IV chord and "men" on the I chord. This amen cadence fits very well to bring a satisfyingly graceful closure to Amazing Grace, letting the congregation to declare a "yes" (ie, amen) to the grace and faith proclaimed in the song.

However, instead of rushing from IV to I, it takes 4 measures to gradually hover and descend home:

- From Ab (IV) to Fm7 (ii), which is the relative minor of Ab. It is to savor a different taste of the suspending IV for one more measure.

- Then the landing begins, first with bass from Ab to G. They respectively support the chord Ab (IV) and Eb (I), giving a foretaste of the homecoming plagal cadence but without the Eb footing.

-

Then, with one step closing to home, it glides to the ii chord Fm7. In modern jazz-influenced music genres, this would conveniently walk through the cycle of fifth to V before hitting home on the I chord. But here the arranger did not take this path. Rather, the chord stays on ii (Fm) for the full measure before landing on the finishing I (Eb) chord. Doing this preserves the overarching plagal IV-I movement. The ii (Fm) chord before the very last bar continues the IV (Ab) chord as its variant - the relative minor. Adding a the 7th to this ii chord (becoming Fm7) is a clever choice as it brings back to original triad of the IV (Eb) chord. Let's spell out the notes of the chords:

- ii chord (Fm): F-Ab-C

- ii chord 7 (Fm7): F-Ab-C-Eb

- IV chord (Eb): Ab-C-Eb

- This move from ii7 (Fm7) to I (Eb) carries the best of both worlds: the graceful IV-I cadence, and the smooth homecoming of the bass line walking from Fm to Eb.

This prolonged cadence lets the audience linger on the ecstasy of the music and to center on the message of the song, savoring the "amazing grace, how sweet the sound", contemplating on their own awakening stories of "was blind but now I see". Such an intimately amazing listening experience!

Summary

As a summary, the chord progression for the Celtic Woman's rendition of Amazing Grace is skillfully arranged. It infuses freshness to the song, setting the well-fitted atmosphere as each stanza develops. Beyond the pleasure of sonorous sensation, the chord arrangement vividly tells the timeless gospel story, powerfully speaking through the ears to their souls.

Chris Tomlin Rendition

Chris Tomlin is a highly acclaimed musician who has left an indelible mark on the world of contemporary Christian music. As a GRAMMY award winner and a top artist on the Billboard charts, his talent and influence are undeniable. Known for his ability to infuse new life into traditional hymns, Tomlin has masterfully recreated timeless songs with contemporary arrangements. His renditions of hymns such as "The Wonderful Cross," "All The Way My Savior Leads Me," and "Amazing Grace (My Chains Are Gone)" have resonated deeply with listeners, blending heartfelt lyrics with captivating melodies. Through his innovative approach, Chris Tomlin has enriched the spiritual experience of countless individuals around the world.

Adding a New Chorus to Amazing Grace

In his rendition of Amazing Grace, he added a new chorus to the original stanzas, converting the traditional 4-phrase melody, stanza-to-stanza format into the contemporary verse-chorus format. To carry the style of the originally repeating stanza, while adding the new chorus, the arrangement follows the AABA song form:

Stanza - Stanza - New Chorus - Stanza

In this new format, the stanza is sung 3 times, with the new chorus inserted between the 2nd and 3rd stanzas. So there are back-to-back stanzas that carry the continual lyrics flow of the traditional version. It also ends with the original stanza, leaving the lingering aftertaste of the traditional hymn.

On the other hand, the added chorus provided a break between the repeating stanza. This functions as the B part in the AABA form, refreshing the ears of the listeners after 2 times of A. Following the uplifted mood of B, the final A becomes more enjoyable as it resolves to the restful ground. The addition of the new chorus further enhances the repeatability of the already welcoming melody.

Changing Time Signature from 3/4 to 4/4

One highlight of this rendition is that the time signature is changed from the traditional 3/4 to 4/4, drastically changing the feel of the song:

A-ma - zing grace how sweet the sound

1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3TO:

A-ma - zing grace how sweet the sound

1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4

See that for both versions, the downbeats land on the same words ("maze", "grace", "sweet", "sound"), but the counting is re-distributed between them.

This change of time has 2 effects:

Effect 1: slower tempo

It may be expected that a change from 3/4 to 4/4 would sound more busy, as one more beat is cramped into the bar. But that is not true for this Amazing Grace arrangement. What was originally 6 beats are now counted only 4 beats, the counting of which now sounds slower. To illustrate this concept, let's say each beat lasts for one second in the 3/4 time signature. Then the first 2 bars ( from "a-ma…" to "how") lasts for 6 seconds. In the new 4/4 time version, the words are sung at the same speed, but the same 6 seconds are equally spread into 4 counts. Each count then lasts for 1.5 seconds. In other words, each beat now lasts longer until the next beat, and therefore sounding slower.

Effect 2: steadier rhythm

Changing to 4/4 time, the distribution of downbeats vs upbeats is more even than in 3/4 time. If we see a downbeat as a strong beat and upbeat a weak one:

- 3/4 Time: strong - weak - weak

-

4/4: strong - weak - strong - weak

(count it slower than in 3/4 due to Effect 1)

The combination of these 2 effects contributes to the steadiness and calmness of this Chris Tomlin version of Amazing Grace. This mood is further elaborated by the use of chords

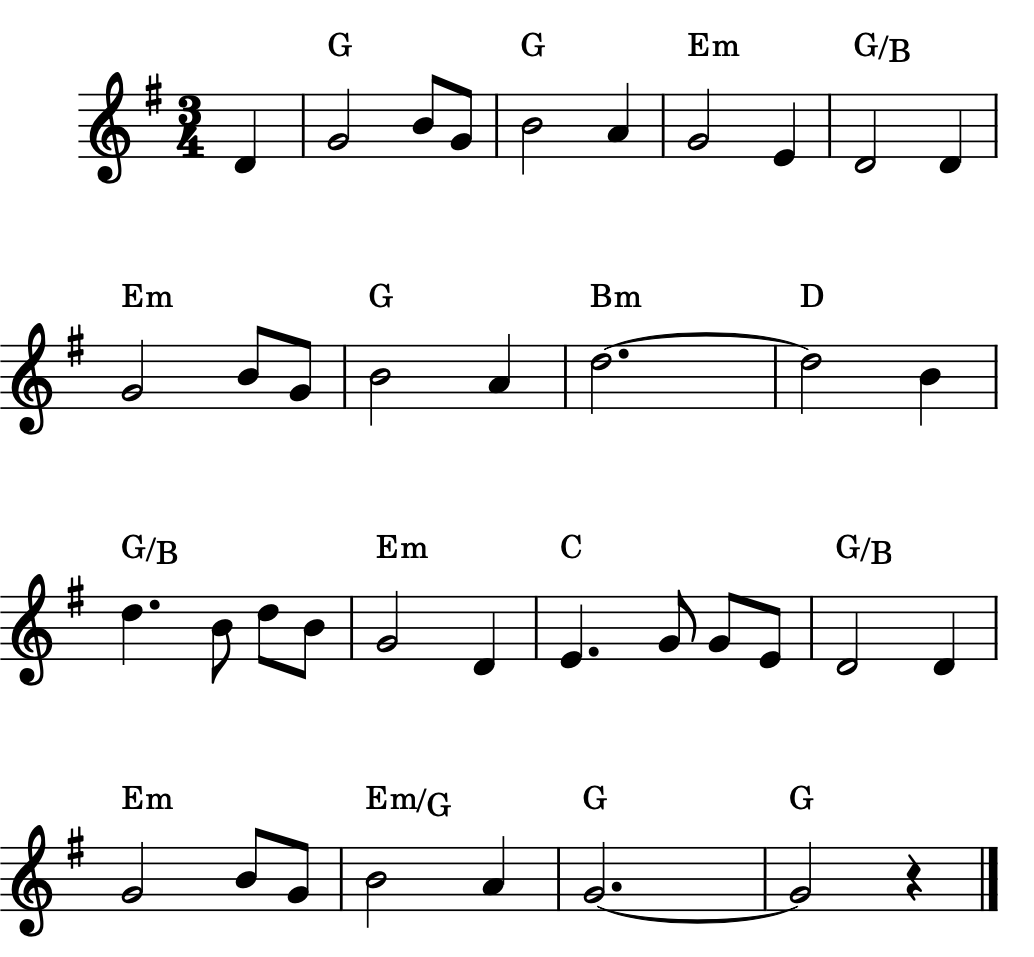

Chords in the Verses

The verse, ie, original hymn melody, stays most of the time on a G chord or chords that are rooted on a G note bass. G is the root chord of the song. Staying on this home note throughout the verse conveys the sense of stability and conviction. This is called a pedaling effect, by anchoring a passage of music - in this case the verse - on the same foundation. Because the chords harmonize consonantly with the G bass (except the D/G chord) and with the melody, this pedaling sets up a constantly stable yet slowly evolving atmosphere.

Chords in the Chorus

Departing from anchoring on the root (or in roman numeral I) of the verse, the chorus loops back and forth between the IV and I chords, ie, C and G. Moving from IV to I as an ending is called Plagal cadence. Looping of the plagal cadence, ie, IV - I - IV - I creates a continual transition between the suspending of IV) and the resolving of I. This is less intensive than a loop of the Perfect cadence V - I - V - I, but creates a comfortable tension-relax movement that can smoothly repeat for a long time. It is a common device to prolong a section of musical passage and to give a sense of lingering.

Here in the chorus, the shifting of tonal center from the root G to the subdominant C supports the uplifting of the melody. In the verse, the melody spans the range of the octave between D4 (major 2nd above middle-C) and D5. In the chorus, this range shifts up a major 4th to between G4 to G5. This uplifting heightens the intensity and therefore perfectly suiting the proclaiming conviction "my chains are gone, I've been set free"!

The end of the chorus brings the full tonal resolution. First it hits the Am7 chorus, introducing for the first time (and the last) a minor chord to this song. It is the ii chord that signifies the entrance into the ubiquitous ii-V-I chord progression. This ii-V-I walks through the circle of fifths back to the home chord I, gratifying the sense of completion at the end of this exalting chorus.

How aptly fitting it is that this ending root chord brings home the words "amazing grace". This also cleverly paths a segway back to the first verse that starts with "amazing grace", using repetition to highlight the theme of the song "amazing grace". The design of all this chord arrangement sweetens the already "sweet sounding" lyrics.

Pentatonix Rendition

The Pentatonix rendition of Amazing Grace compiles both the traditional version (in 3/4 time) and the modern Chris Tomlin version (in 4/4 time) that includes the added "My Chains Are Gone" chorus. It goes through multiple key changes, not only to match the vocal range of the singers but also for music development:

- Verse 1: Matt Sallee - E major

- Verse 2 & Chorus: Scott Hoying - E major

- Verse 3 & Chorus: Mitch Grassi - B major ( a perfect 5th higher than the previous verse)

- Verse 4 & Chorus: Kristin Maldonado - High E major ( an octave higher than the original key )

- Coda: Kevin Olusola - High E major

Therefore this song has both changes in the time signature and in the key signature. The arranger did an excellent job smoothing the transitions of all these changes without any distraction while still engagingly carrying upward the audience's emotion along the dramatic ride. Let's look at how it is done.

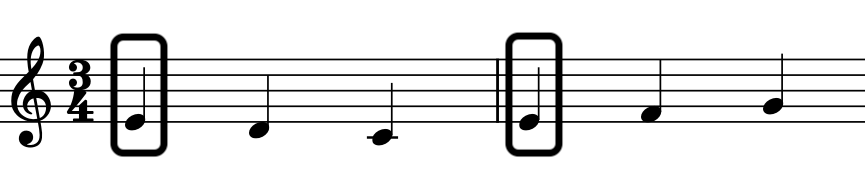

Time Signature Change

The time signature changes from 3/4 in verse 1 to 4/4 in verse 2. When in the same tempo, 3/4 sounds swifter and lighter weight than 4/4. It is because the next downbeat (beat 1) comes earlier in 3/4 than in 4/4. It only takes 2 other counts, ie beat 2 and 3 to loop back to the next beat 1, while it takes 3 counts for 4/4.

The 4/4 time verse in this Pentatonix version (which is a cover of the Chris Tomlin version), however, is not the case. It is because instead of spreading the original 3/4 measure to the longer 4/4 measure, two 3/4 bars (ie 6 counts) are compacted into one 4/4 bar (ie 4 counts):

In 3/4 Time:

A-ma - zing grace how sweet the sound

1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3

In 4/4 Time:

A-ma - zing grace how sweet the sound

1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4

These are 2 very different moods. To smooth out this transition between verse 1 (in 3/4 time) and 2 (in 4/4 time), a number of devices are used:

-

De-emphasis the Rhythm:

De-emphasis the rhythm sense to minimize the rhythmic accents in verse 1. When counting is clumsy and confusing across the 2 verses, just skip it. But how? It's achieved by muting percussive sounds in the music and smoothing out the attack envelope on the vocals. -

Pedaling:

Long holding the root note throughout the whole verse (aka pedaling). This erases movements and hence the rhythmic accent. -

Slower Tempo:

Use a slower tempo in verse 1 than in verse 2. This further dilutes the sense of rhythm of verse 1 and thus the need of transitioning the change in beat counting. -

Overlapping:

Changing the time signature on the last measure of verse 1 instead of waiting until the start of verse 2 to do it. This overlapping of the 4-count bar onto the 3-count one smooths out the transition, combining the full 3-count of verse 1's last note (on "see") and the 1-count pickup note of verse 2 (on "Twas"). -

Clear Counting:

The vocalized beats in verse 2 clearly spell out each count of 1-2-3-4. This is to assist the listener's rhythmic pulse transiting into verse 2,. It acts as the metronome of the now accelerated verse for a better hand-holding. This contrasts the almost motionless long pedaling of verse 1, entering the elevated modernized verse 2 on the new beat.

4.3.2 Key signature change

Take notice of the climb from verse 2 to verse 4:

- Verse 2: E major

- Verse 3: Up a perfect fifth to B major

- Verse 4: Up a perfect forth to E major (an octave higher than verse 2)

The 5-step up from verse 2 to 3 typically brings the male vocal range (by Scott) to a female one. But instead of being sung by Kristen - the only female voice in the group, verse 3 is led by Mitch Grassi with his outstanding high tenor voice that powerfully projects in this range. This energizes the song to a new level.

Then comes the climax of the song - verse 4. It is an octave higher than the starting E major key in verse 2, being the brightest part of the song at the chorus. This brightness continues in the coda by Kevin's silky falsetto. Without a rhythm section, the coda intensity softens, gracefully ending the song with the gentle brightness that declares "was blind, but now I see"

Chords for Key Modulation

Verse 2 to Verse 3

In Pentatonix's Amazing Grace, the first key modulation goes from verse 2 (E major) to verse 3 (B major). It happened discreetly because most notes exist in both the keys:

In E major: E F# G# A B C# D#

In B major: B C# D# E F# G# A#

All except one note are the same between the 2 keys. The only difference is the A note in E major and the A# in B major. The transition uses the IV-V-I chords of the target B major, ie,

E ⇒ F# ⇒ B

To smooth out the transition, inversion of the chords are used, becoming:

E/G# ⇒ F#/A# ⇒ B

This is done so that the bass line walks up the B major scale to land on the new key of B. See that the A note in the original key (E major) becomes A# in the new key (B major). This changes the scale

FROM:

E F# G# A B

TO:

E F# G# A# B

This raising of the 4th note of a major scale (1 2 3 4# 5) characterizes a scale called "Lydian mode", which appropriately infuses a sense of elevation and mystical hope into verse 3 "The lord has promised good to me".

Verse 3 to Verse 4

The second key change happens between verse 3 and 4, from B major to the high E major. While the principle is to use the dominant (5th) chord of the target key (typically adding the 7th to the chord), it is interesting that in this song the originating key (B major) is already conveniently the 5th of the target (E major). So a natural choice of the modulation chart is a B7.

However, using a B7 chord here blemishes the perfect cadence at the end of verse 3, especially when the leading voice lands on the root B note and clashes with the added A note of the B7 chord. So which chord can be used for this B major to E major key change?

To solve this, the arranger cleverly placed a NC, which stands for "no chord" on the last note of verse 3. Since using the supposedly suitable chord B7 creates a problem, why not just not place a chord at all? Doing so mute any harmony on that note. So all of a sudden, all accompaniment is dropped, leaving the lead voice as solo standing out for 1 beat.

Then in this skillful arrangement, the anticipated B chord surprisingly comes back on beat 2 of the bar. But now instead of being the homecoming root chord of verse 3, this B chord functions as the transitional dominant chord of the target E key of verse 4:

| NC B C#m7 B/D# | E |

This walking bass of B C# D# E acts as both the 1-2-3-4 (do re mi fa) of the old key and the 5-6-7-8 (sol la ti do) of the new key. All these 4 chords exist in both keys unmodulated. This dual-identity makes the transition unnoticed, while powerfully shifting the key up a 4-step interval to prepare for the climax of the song.

This arrangement is demanding to the performers, because the undetected transition lacks the signal that the key is changed. It challenges the vocalists to orient themselves to the new tonal center of the new key. As a note to music directors for congregational singing, use this kind of modulation with caution as the congregation usually needs a strong hint of what key they are about to sing in. But this is not a problem for Pentatonix. Here Kirstin Maldonado hits the first note on the new key with great confidence, beautifully uplifts the musical scene onto a new ground.

Chorus Density and Arrangement Chords

Let's compare Chris Tomlin's version of the chorus to Pentatonix, using Pentatonix's last chorus:

- Here "CT" stands for Chris Tomlin

- "PX" stands for Pentatonix

- Beat count under the lyrics

CT: IV I/iii

PX: NC IV V iii vi

My chains are gone, I've been set free

4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3

CT: IV/vi I/v

PX: I IV V/IV iii I/iii

My God, my Savior has ransomed me

4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3

CT: I/iii IV I/iii

PX: vi IV V VIsus VI (hold)

And like a flood His mercy reigns

4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3

CT: ii V

PX:NC ii V

Unending love

4 1 2 3

CT: I

PX: NC IV/i I

Amazing grace

4 1 2 3 4

Difference in Chord density

Comparatively, Pentatonix has 2 times the number of chords than Chris Tomlin's:

- Chris Tomlin: total of 10 chords in the 8-bar chorus, most of them are on beat 1,

- Pentatonix: chords on 17 chords, which are on both beat 1 and beat 3. If the 3 NC (No Chord), there are 20 chords.

The Use of No-chord

Pentatonix uses multiple "No Chord" (NC). A "No Chord", being an absence of music between the surrounding chords, can be as musically moving as a present chord. In fact it can be even "louder" than a present chord because the sudden drop of music creates an immense contrast that draws more attention than the progression of chords.

Looping Through Parts of the Circle of 5th:

Pentatonix loops through 4 chords along the Circle of 5th. In music theory, Circle of 5th consists of chords 4 steps above (or 5 steps below) its previous one, eventually leading to itself coming on a full circle. The 4th-interval between the neighboring chords has a strong suspend-resolve pull and therefore linking a 4th-interval one after another daisy-chains the chords in a musical flow of continuous cadence.

One arch of the Circle is IV-vii-iii-vi. But vii, being a diminished 5th chord is not commonly used in contemporary pop music, is usually replaced by the V or V7 chord because of the notes they share. Therefore this arch of chords becomes IV-V-iii-vi. This also balances the number of major and minor chords, with IV and V being the 2 major chords while iii and vi being the minor chords.

Here Pentatonix loops through this IV-V-iii-vi progression and its variation 3 times:

- IV-V-iii-vi

- IV-V-iii-I/iii-vi

- IV-V-VIsus-VI

On the contrary, Chris Tomlin's chord looping is a very different approach. It mainly loops on only 2 chords: IV and I. They are also the neighboring chords on the Circle of 5th, being 4 steps apart. As discussed above, this forms a loop of the Plagal Cadence.

Furthermore, Pentatonix loops through this IV-I progression and its variation 3 times:

- IV - I/iii

- IV/vi - I/V

- IV - I/iii

Difference in Mood

All of the above usages of chords contribute to the difference in the mood of the 2 versions.

Pentatonix's version goes through more changes of emotions:

- Major - major - minor - minor

- More frequently : 2 times per bar

- Use of V chords, which builds up the gravitational pull to the root chord I which finally arrived on the last bar.

- Use of NC to create even bigger contrast in the flow of chords

Comparatively, Chris Tomlin's is more steady in the mood

- Mostly major chord

- Mostly the IV and I chords, which form the gentler Plagal Cadence

- No use of V chords in the first three quarters of the chorus, therefore less pull to the homecoming root chord I

It is important to know that not which one is better. Using denser chords does not mean it is better than using less chords - or vice versa. Same for the use of no-chord. They are just different in terms of creating the musical spac. What matters is what sonic picture you what to depict using these devices.

Summary

To summarize, with higher musical ground lifted by the modulation into verse 4, the dense chords, no chords and the intense mood swinging chord progression loops all provide a musical-emotional framework to bring the song to the climatic chorus. It declares the powerful message of liberation - "My chains are gone, I've been set free. My God my Savior has ransomed me"!

Using Chords to End the Song

To wind down the climax to soothing ending, this song takes a twist of chords at the end of the 3rd line "His mercy reigns". Landing and holding on the major VI chord (ie C#) from the previous V chord, it creates a deceptive cadence.

Multiple actions are going on here:

- B to C#sus chord: this V chord (B) to the vi (C#m) is a deceptive cadence - an unexpected direction that misses the root I chord that V normally heads to

- C#sus to C#: this brings another surprise, because it introduce a new note (F or E#) outside of the current E key. The unexpected C#m cadence becomes an even more unexpected C# major. This temporarily modulate the song to C# major! The new note E# lifts the original root note E by half a step. This further elevates the climax to the tranquil pinnacle of the song.

- Pausing on C# (fermata): The reason why this pinnacle is tranquil is that the music softens and decelerates to a long pause at this point. This lets the sensation ring and settle in the listener's ears.

Then to bring this chorus to the full closure

- NC after that: this no chord creates a break to rest. From ears to their heart, this lets the listener soak in this restful high ground and be in awe in this scene of the out-of-the-world spiritual reality of the Grace amazing!

- F#m and B after that: after the temporary modulation to C#. The VI chord naturally walks down to ii chord (ie F#m), following the circle of 5th to prepare the entry to the familiar ii-V-I song-ending progression.

- Another NC: the final landing to the last note of this chorus comes yet another No Chord. This no chord on the downbeat highlights the lyrics "Grace" by retreating all the music except the leading voice. As the intensity of the music softens along the previous bars, this no chord gracefully brings the song to a moment of calming stillness.

- A/E to E: at last, the ending is ornamented with a IV-I plagal cadence. Instead of overlapping the IV chord to the last note, doing so would unsettle the well-prepared landing to satisfaction, and also would undo the stillness of the no chord, the IV chord is placed after the downbeat. This accent on the upbeat (beat 2) magnifies the suspense of the IV chord in the cadence, landing the resolution on the final I chord on a more solid ground, especially here with the bass line pedaling firmly on the root I note. Also, as a choral tradition in Christian faith community, a vocalized "amen" is commonly added to a hymn to close the song with an affirmation. This "amen" is harmonized in the form of IV-I plagal cadence. So this is not a coincidence here that a IV-I progression is appended to the end of this chorus.

All these beautifully orchestrated move of the chords in the last 3 bars - from the pinnacle of the modulated VI chord on "His mercy reigns", to the no-chords that sooth down the mood and highlight the "Grace", to the reaffirmation of the "Amen" after "Amazing Grace" - not only bring the sweet closure to the song, but also bring reassurance that "This grace that brought me safe thus far, and grace will lead me home". Amen! Amen!